With Canada’s aging population, many healthcare professionals are nearing retirement and by 2022, it is estimated that Canada will be significantly short of nurses. Although the total supply of regulated nurses reached 448,044 in 2020 with only 41,967 unemployed; the demand for more nurses will likely not be met by the supply of Canadian nursing graduates for several years. However, this void can be filled if more internationally trained nurses become licensed to practice in Canada.

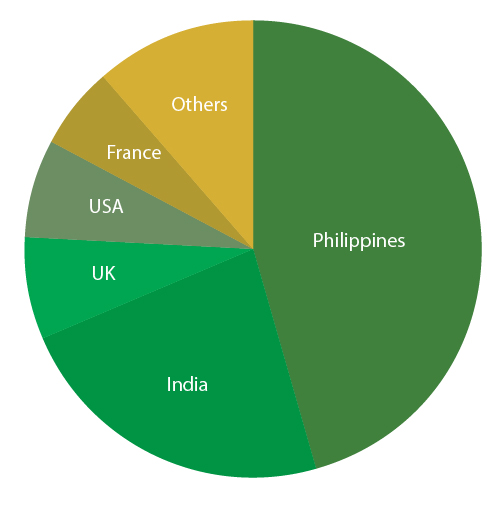

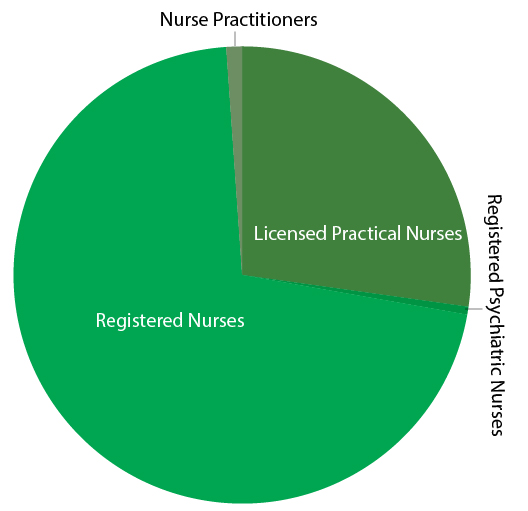

The Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI) confirmed that as of 2020, there were 304,558 Registered Nurses (RNs) licensed to practice in Canada. The percentage of internationally educated RNs in Canada remained stable over the previous five years, at around 9 per cent. British Columbia had the highest percentage of Internationally Educated Nurses (IENs) at 14 per cent, followed by Ontario (11 per cent) and Alberta (10 per cent). CIHI further reported that the top five countries of graduation for regulated IENs are the Philippines, India, United Kingdom, United States of America and France.

Immigrant Muse Magazine (IMM) is unable to provide the ratio of foreign educated nurses to regulated IENs . Efforts to obtain data on the number of foreign nurses who have immigrated to Canada in the last five years from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) proved abortive.

CIHI’s 2020 report shows that, averagely, there are only 774 registered nurses per 100,000 people in Canada. While Yukon has the highest number of registered nurses to population at 1,103; Ontario has the lowest number at 609.

The National Nursing Assessment Services (NNAS) reports that in the last five years, 40,249 Advisory Reports were issued for about 20,000 foreign trained nurses seeking licensure. This shows an average of two reports were issued per applicant since applicants can apply for more than one profession and/or jurisdiction. Gayle Waxman, the Executive Director of NNAS discloses that the top five countries of applicants are India, Philippines, United States, Nigeria, and the United Kingdom.

Why is there a shortage of nurses in Canada despite the influx of foreign trained nurses?

It is not because immigrant nurses don’t want to practice, but because the nursing licensure process is distinct and separate from the immigration process and can sometimes become an unending circle of applications, rejections and failures that require a lot of time, money and energy.

Many unlicensed immigrant nurses who have been in Canada for more than a year sometimes encounter difficulty in completing their bridging studies and registrations within an acceptable timeframe. This is often due to changes in the qualifying requirements between the time of landing in Canada and clearing all the processes.

Phyllis Aidoo arrived in Canada seven years ago from Ghana. She landed in Ontario with a Bachelor of Nursing degree and 10 years of work experience as a nurse in her home country. She had passed the English as a second language test prior to migrating to Canada.

At the time she arrived in Canada, the exam she needed to pass to be licensed was the Canadian Practical Nurse Registration Examination (CRNE). Unfortunately, she was short of 15 marks to pass the exam. Shortly thereafter, the licensing exam changed to the National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX).

Phyllis had studied for the CRNE on her own but later realised that had she trained under a Registered Nurse during her first year, she would have been better positioned to pass the exam. But since she had already attempted the exam once, she learned that this option was no longer available to her.

Phyllis has now moved with her family to Alberta and has been studying to complete the various courses and training needed for her licensure. While she is allowed to write her exams from Alberta, she is required to be in Ontario to complete her clinical training, and earn 1,125 work hours to be eligible to practice as a nurse in Alberta.

She is currently working in the education sector until she is able to practice as a nurse.

Phyllis’ experience is common for many foreign trained nurses seeking licensure.

Nursing is regulated in Canada in order to assure the public that nurses meet an acceptable standard of care and practice. Both Canadian and internationally educated nurses need to get licensed to practice in Canada. In 2018, CIHI reported that 80% of Canadian trained nurses obtained their license within two years of graduating. While there is currently no data on the percentage of IENs who obtain their licensure within the same time frame, we believe that IENs take longer to obtain their licensure.

Despite the challenges IENs face in their licensure process, it is not an impossible feat, as shown by the 25,444 licensed foreign trained nurses in Canada.

LICENSURE PROCESS FOR INTERNATIONALLY TRAINED NURSES IN CANADA

Advisory Report

Internationally educated nurses who wish to practice in Canada must first apply to the National Nursing Assessment Services (NNAS) for an Advisory Report. This report enables the regulatory body in each province and territory to determine if the applicant has met all the requirements to practice in Canada, or if there are gaps that must be addressed.

Visit NNAS website for the current application process, required documents and fees to obtain your Advisory Report and get all necessary documents ready to avoid wasting time.

NNAS will issue an Advisory Report to both the applicant and the regulatory body of the province the applicant chooses once the assessment is complete.

The first application which is referred to as the Main Application Order is valid for 12 months and costs USD $650 (equivalent to $815 CAD). If for any reason the process goes beyond 12 months, applicants would have to pay the same fee again to continue the assessment unless they renew their application before it expires.

During this process, if applicants wish to obtain an Advisory Report for a province other than the one they initially applied for, they will have to pay additional fees. Once the provincial regulatory body receives the Advisory Report, they will advise the applicant of the next steps.

If the regulatory body determines that there are gaps in the applicant’s education and training, they may recommend taking a bridging course to make up for the gaps.

If further training in nursing or a bridging course is required to fill any gaps in education, there are several colleges and universities that can provide the training.

For instance, in Ontario as many as 25 universities and colleges offer nursing programs such as, Bachelor of Science in Nursing or Bachelor of Nursing. Upon completion of these courses, applicants will write the National Council Licensure Examination (NCLEX) to be able to practice.

Processing time and cost of licensure vary from province to province.

In Nova Scotia, the Nova Scotia College of Nursing (NSCN) determines the eligibility of each applicant to pursue licensure. If an applicant falls short of the requirements, they will be required to take the Substantive Equivalent Competence Assessment (SECA) and/or a nursing re-entry program.

According to Jane Wilson, Communication Consultant, NSCN, “IENs whose nursing education and credentials are comparable or somewhat comparable to Canadian nursing education and who meet all of the registration and licensure requirements can get registered and licensed within 8 weeks. Those whose education and credentials have been deemed non-comparable require some bridging education courses or a competence assessment before they can be eligible for registration and licensure. The length of time to complete these is unique to each applicant.”

Currently, there is a 20 per cent vacancy rate for nurses in NS, as such getting a job after licensure is generally easy.

If you are a nurse outside Canada looking to get licensed to practice in Canada, you can access the Pre-Arrival Supports and Services (PASS) for nurses to prepare you for licensure to practice in Canada.

Pre-Arrival Supports and Services (PASS)

PASS is a federal government funded program that provides services to internationally educated nurses wishing to migrate to Canada prior to their arrival here.

Meghan Wankel, Programme Coordinator at PASS explained its role to Immigrant Muse.

Q. Is PASS funded by the Ontario government, and are your services only for those planning to settle in Ontario?

A. Unlike CARE Centre’s STARS Program, which is provincially funded and only available to nurses seeking licensure in Ontario, PASS is federally funded by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC). PASS is a pan-Canadian program, so we work with nurses going to every province and territory in Canada.

Q. Do your services extend to nurses who have already arrived in Canada or only for those planning to/have received clearance to migrate to Canada?

A. PASS is entirely only pre-arrival and the program does end once participants land in Canada. To join PASS, nurses have to be outside of Canada and must have been approved to migrate to Canada as a Permanent Resident. We are unable to help people migrating on work, student or visitor visas.

Q. Are there any services for nurses who have already arrived in Canada and need help?

A. Since PASS is only pre-arrival, once nurses land in Canada, they are referred to post-arrival supports in their destination province, which includes settlement agencies as well as programs that specifically assist internationally educated nurses. Nurses who arrive in Ontario are referred directly into CARE Centre’s post-arrival program, STARS. You can read more about STARS at www.care4nurses.org (click on the right side “STARS” box)

Q. What are the non-licensed healthcare professions that nurses could work in, until registered?

A. This is not a comprehensive list, but below are some typical jobs that internationally educated nurses (IENs) can pursue while meeting their nursing regulatory requirements:

- Personal Support Worker / Health Care Aide / Critical Care Aide

- medical administration (may or may not require certification; will specify in job description)

- public health teaching/working on health issues for a non-profit agency

- pharmaceutical sales

- health research

- health informatics

- health roles on construction sites (first aid officer, daycare coordinator, medical file administrator)

- nanny

Visit PASS website to learn more about their services.

The importance of extensive research and networking with a support group cannot be overemphasized if you are looking to practice nursing in Canada as a foreign trained nurse. Check with the regulatory bodies of at least three provinces of your choice to ask questions, connect with the nursing association in the province to find IEN mentors and allocate the necessary resources (time and money) from the start of your licensure process.

Phyllis, whose experience was shared earlier says that at the time she migrated, there wasn’t enough information for new immigrants in the healthcare sector to learn about all the requirements they needed to qualify to practice.

Given Phyllis’ experience, she advises that, if at all possible, it’s best to concentrate on taking the necessary courses instead of working, as that would help quicken the process. While she had studied on her own, she recommends joining a college to complete the necessary courses.

Phyllis is prepared to mentor those needing more information. She noted that if there had been more networking opportunities, it would have helped her in her journey of becoming a qualified nurse in Canada.

The 150 Nurses for Canada group includes strong public advocates and leaders. They inspire passion for nursing through their support of professional development by being mentors or advisors. Visit their website to find mentors and advisors in your province.

Regulatory Bodies in Each Province and Territory

Sources

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Nursing in Canada, 2020 — Data Tables. Ottawa, ON: CIHI; 2021.

Canadian Nurses Association

National Nursing Assessment Services (NNAS)

Contributors: Harita Dave, Oyin Ajibola